Happy New Year!

I started blogging roughly four years ago with several goals in mind, one of which was to spend more time reading the literature. There is no question that blogging caused me to read more. But last January, Meg Duffy posted about her progress on her goal to read 260 papers in 2015,* and that made me wonder: how many papers do I actually read in a year?

I’m a big fan of tracking my personal productivity by keeping a time journal, so Meg’s idea for keeping an academic reading journal was instantly appealing. And thus I wrote down every paper that I read in 2016. I learned a lot about my work habits by doing this, so I decided to write a post about the experience, in case some of you are also interested in giving it a go in 2017.

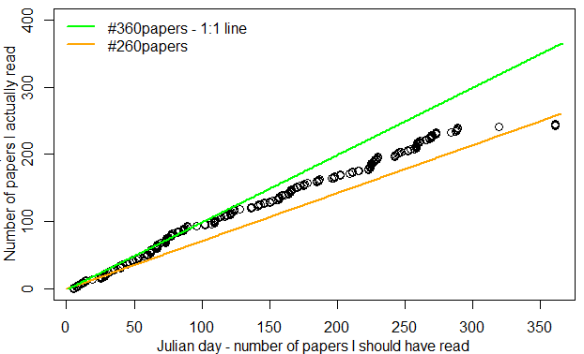

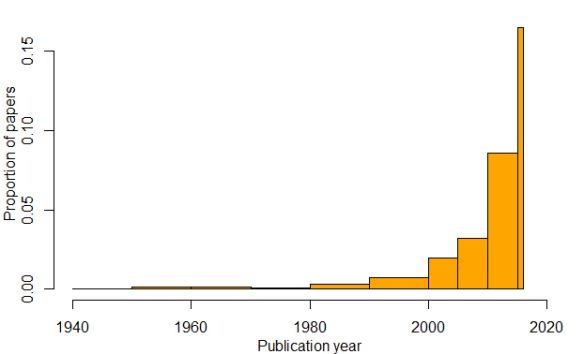

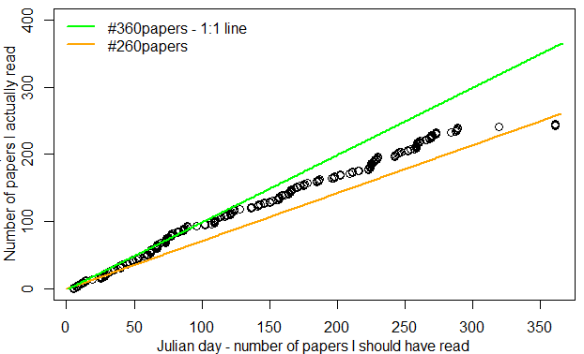

Like Meg, I only recorded the papers that I read thoroughly (i.e., to the level that I would read a paper for a lab meeting). I must have skimmed at least three times as many papers as I actually read, especially during periods where I was reading to prepare to write grant proposals and manuscripts. To get an idea of how consistently I read thoroughly, I made this plot of my paper-reading timeline for 2016. I made an Excel spreadsheet that automatically updated this plot every time I added a paper, which helped me to track my progress.

My goal was to stay above the orange line all year, and I pretty much succeeded! As I write this post on 28 December, I have read 245 papers, leaving me 5 papers/day if I really want to reach my #260paper goal by December 31st. That’s not too bad! I would have surpassed my goal if it wasn’t for fall field season. Unsurprisingly, I gave up reading (and regular showers and normal eating habits) for a few weeks of intense data collection, as I do every year. I wish I had kept up with reading during that time, but oh well.

You might be wondering which journals are most frequented by a self-proclaimed parasite ecologist. Of the 245 papers that I read, there were only 12 journals that showed up five or more times: Conservation Biology, Ecological Applications, Ecology, Ecology Letters, Journal of Animal Ecology, Journal of Parasitology, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, PNAS, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Science, TREE, and Trends in Parasitology. There weren’t any huge surprises there, except maybe Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, which had some excellent and recent special issues that I dug into.

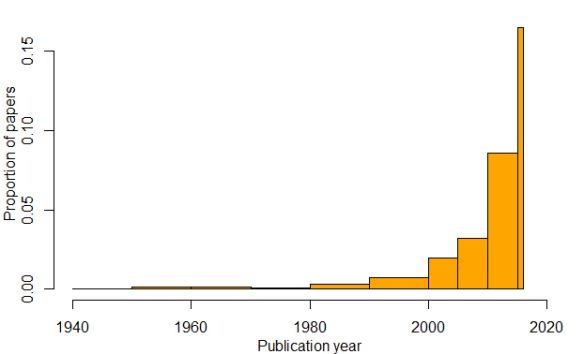

Also unsurprisingly, most papers were recent, with ~16% of papers published in 2016. I did read some older papers, but I want to do a better job of digging into the older literature in 2017 – partially because I think it’s important, and partially because it’s fun! (The bin sizes on this figure are purposefully uneven.)

I also kept track of why I read each paper, though I don’t think most of those data would be interesting to people besides me. I was somewhat surprised to find that only 19 (8%) of the papers that I read in 2016 were specifically for blogging purposes. It seemed like blogging increased my reading by so much more! But an additional 20 papers were stuck under the heading of “other reading,” and many of those could have ended up on the blog, but for whatever reason I decided not to write about them. Finally, I was not surprised to find that the most common reason for reading a paper was preparing for grant writing. Because it was a busy grant year, grant preparation accounted for a whopping 42% of the papers that I read.

So there you have it! I’d be interested to hear your suggestions on how best to spend my reading time in 2017. Anyone have some neat “old” parasite ecology papers to suggest?

*#365papers was co-founded by Jacquelyn Gill.